Several days after the Port of Seattle announced a “possible” cyberattack on its systems, Seattle-Tacoma Airport is still largely offline, causing chaos among travelers and acting as a standing warning against taking cybersecurity lightly. Ask me how I know.

The outage resulting from the recent hack has not, fortunately, caused planes to fall out of the sky or Air Traffic Control to double-book a runway. Those resources, run by the feds, are considerably more locked down.

Rather than catastrophe, what we have now — and for the foreseeable future, since authorities have offered no timeline for restoration — is an object lesson in why we have rules about where we put our eggs.

For my part, I found out on Sunday when — and I hesitate even to mention it, because no one seems to know about this miraculous service — I went to reserve my place in the security line via the SEA Spot Saver. The service was offline, and throwing the kind of error that you don’t have to be a sysadmin to know means deeper problems.

If I had been a good reporter and read my own publication over the weekend, I would have known this was the result of, among other things, the entire user-facing DNS configuration of the Port’s web architecture being totally cooked. (The Spot Saver site is still offline, but the function has been resuscitated by Clear for now.)

Luckily I was not checking a bag and security was light, possibly due to a jackknifed semi blocking all southbound traffic on I-5.

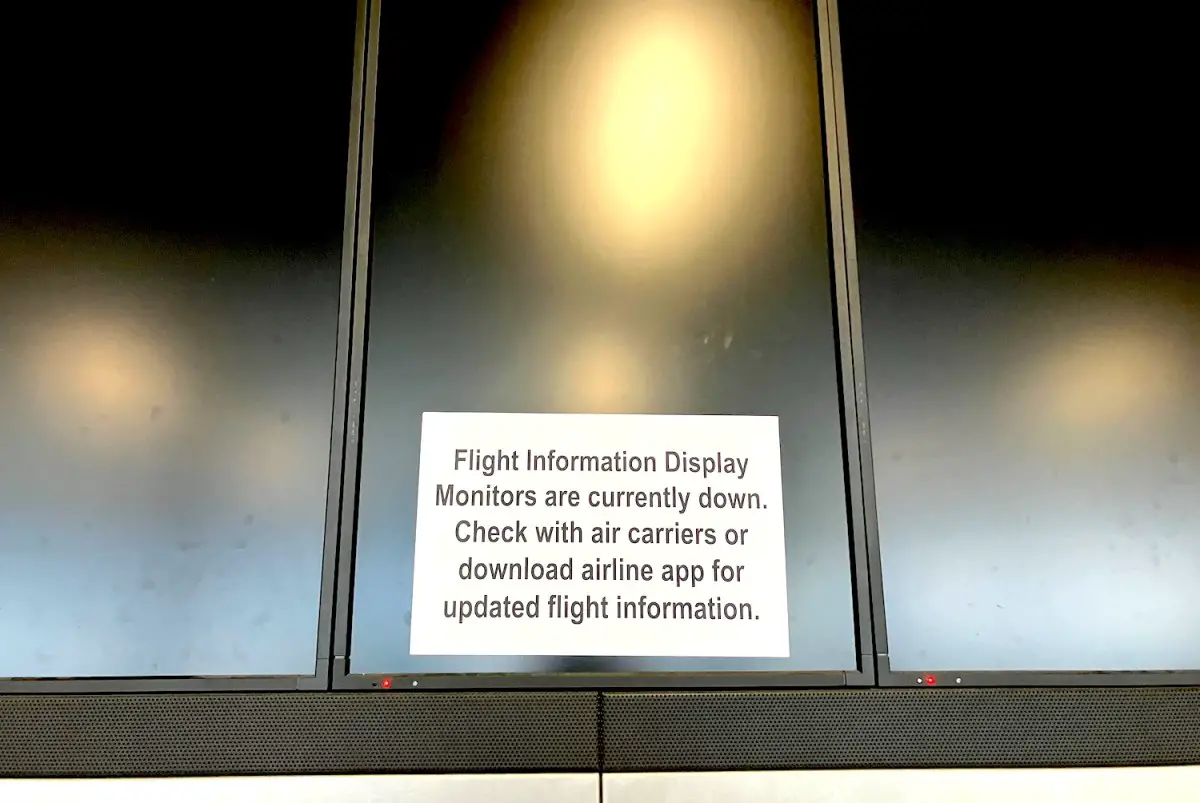

At the airport, the large screens one would ordinarily loiter under to find one’s flight were ominously dark. But considering the endless construction at Sea-Tac, I chalked this up to electrical work.

It was only at the “S” gates that the extent of the problem became clear. Every screen in the area was dark; the TVs above the waiting areas, the multi-display arrays directing travelers to gates, the monitors of the gate agents and the gate info displays themselves.

Though my boarding pass had directed me to a gate, there was no way to be sure that was the correct one, so I checked with the agents there. They confirmed it, and I asked about the hack.

“It definitely is a bit of a… show,” the airline agents agreed, politely eliding the same part of the word I had. All airport systems shared by multiple airlines were down. Baggage handling, they said, was getting the worst of it. The agents were (tell no one!) ignoring their own baggage size rules and didn’t bother collecting “volunteers” to gate-check bags and speed up boarding. Inter-airline communications were labored.

The gate desk was mostly offline, I was told, as it’s a shared system between Alaska, Delta and anyone else who comes to the “S” gates. The gate was unable to display the flight number, boarding groups or any delays — a half-hour for my flight — except over the public address system — which was extremely competitive due to the need to constantly repeat current gate numbers. Nearby, one gate had paper signs announcing the flight that had last departed, though that was obviously hours earlier. (Sea-Tac airport spokesperson Perry Cooper told me in an email that my experience was “not typical of the rest of the airport.”)

The tablets for checking people in were working, “but limited,” the agents said. Changing flights or seats was not happening. (“I think maybe I got upgraded to first,” I ventured hopefully, but they just shooed me away.)

In situations where the digital infrastructure crashes, it can happen that those who cling to analog resources look smart rather than quaint. Not so today. As I waited, every few minutes someone would walk up to the gate with a paper ticket telling them this was where they departed. Some were lucky enough to be told it was just a few steps away, while one unfortunate soul was redirected all the way to the “N” gates — the polar opposite, as you may imagine, of the “S” gates.

The solution, as proffered by gate agents and paper signs taped to blank displays alike, was to use the app. But it’s precisely because of problems like this week’s that no one can ever really trust “the app,” because “the app” is as likely to get the hacker treatment as the rest of the Port.

What was extraordinary was that a suspected malicious hacker was able to tank so many systems in one go. We don’t have to expect that the baggage direction, gate guidance and security handling can’t be completely siloed and separate. This is an airport, not a nuclear power plant.

Yet at the same time it seems wrong that the resilience of the system is so lacking. Sure, the airport intranet might go down — but the full-on public-facing website? Baggage routing and gate updates, too? All on the same network? We’ve understood the necessity of breaking apart critical systems for centuries, and have built it into our power and network infrastructure so that when one person runs two hairdryers at the same time, it doesn’t knock out the whole neighborhood.

I’m not complaining because I was inconvenienced. To be honest, this airport trip was no better or worse for me personally than any other. But I saw countless people being put out due to what amounts to badly secured, probably woefully understaffed government IT infrastructure.

When the feds talk about refurbishing critical infrastructure, this is what they’re talking about. Yes, it’s also the ’80s-era computer running on COBOL that controls the traffic lights, dams or missile silos. But it’s events like this — not so much the recent CrowdStrike outage debacle, actually — that really show the soft, vulnerable underbelly of local and national systems. Critical infrastructure, like airports, have a disturbingly large attack surface that have comparatively few resources dedicated to their upkeep.

It’s not that an airport isn’t as valuable of a target as, say, a financial institution or a data broker, but that’s changing. Ransomware, for instance, has proven highly profitable and easy to automate, and AI (you knew it had to figure somewhere) is supercharging credential theft via spear-phishing operations. All this to say that the trend of unlikely targets — schools, libraries and hospitals — being held to ransom is only going to intensify — but these attacks can be prevented, just as they can in private industry where they have expected them for decades.

Anyone traveling through Sea-Tac should definitely budget a bit more time to get through the airport and install the relevant apps. State and city authorities are doing their best to keep everyone informed on this crisis page.