Donations Make us online

Christine Pamela is the CEO and founder of Mestrae, a Malaysian brand for interchangeable footwear.

Disclaimer: The opinions and statements shared within the contents of this article are solely the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of Vulcan Post. All of the details in the content were also shared with us in good faith.

Coming from a high-tech engineering background, I founded Mestrae Interchangeable Heels as a fashion-tech solution for women on the go, and in the larger pursuit of exploring wearable tech for women.

Our brand grew to 31 countries, established a retail presence in Malaysia, Spain, and the UK, and formed direct partnerships with European distributors.

D2C customers from the US accounted for 70% of our customer base and we exceeded our Kickstarter goal by almost 200%.

We captured the attention of the fashion world in New York, and were also recently invited by the US embassy to set up a distribution hub. Mestrae was recognised with a global innovation award and named one of Malaysia’s top startups by the Prime Minister in 2018.

But beneath the surface of the iceberg of startup success lies a world of struggles.

Startups face distinct challenges such as building a new product or service, entering an untapped market, and unstable revenue.

However in Malaysia, startups also face additional challenges of classism, corruption, and racism from government agencies that control early-stage startup funds.

Startup funds by government agencies are often given as “reimbursement” or “matching” grants, requiring entrepreneurs to have a significant amount of funds in their bank accounts. This can be a major obstacle for middle-class entrepreneurs.

Grant agencies implement multiple “SOPs” that perpetuate classism and other discriminations. In this article, I want to share the oppression and abuse I faced from these agencies.

On the surface of the iceberg

As I started building my startup from scratch, I secured inception grants from two agencies, PlatCOM Ventures and Cradle Fund, but the initial deposit was small due to it being a reimbursement grant.

I had to rotate between agencies to spend and claim the funds while meeting all required tasks.

Compared to my direct competitors in the US, Germany, and France who have raised millions of dollars, I received only 6.5% of the pre-seed stage funds that my US competitor raised.

To cover expenses not included in the grants such as overhead, I borrowed money from friends with the plan to repay them once sales were generated.

Unfortunately, these costs are not covered by grant agencies due to the assumption that all entrepreneurs in Malaysia are criminals, untrustworthy, and will misuse the funds.

We completed the inception phase, were recognised as a top startup by PlaTCOM, and were awarded a spot on Cradle’s Wall of Fame.

Our initial sales were successful, but due to our newness to the market, our pricing was incorrect and our supply chain was disorganised.

We learnt quickly about international sales as digital commerce globalised businesses in a snap. Our customers provided us with valuable feedback that helped us improve our offerings but we required seed funding to make progress on tech upgrades and significant fine-tuning.

Nine months after launch, we were awarded the seed-stage (Phase 2) grant from PlaTCOM.

However, to cover additional expenses and comply with the reimbursement mandate, I had to take on heavier personal debts and extend credit from vendors.

Compared to our US competitor, we received only 0.54% of the fund in deposit. Even with a fully disbursed grant, this would only benchmark us at 4.3% of global seed-stage funding.

Despite financial limitations, we produced innovative interchangeable heel technology that rivaled our German competitor and outperformed the rest. We expanded, streamlined our supply chain, and reduced production costs by 30%.

We also broadened our international retail presence and received distribution requests from three countries, fulfilling one. Our small team covered essential areas such as technology, operations, manufacturing, design, sales, and marketing.

The world of struggles beneath

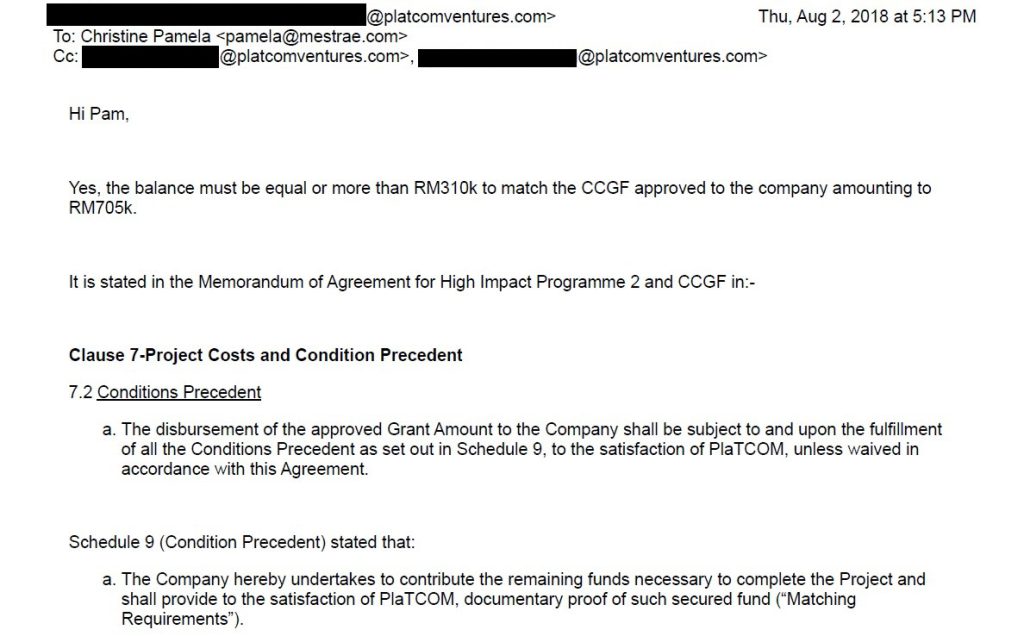

Unfortunately, even with the significant and public accomplishments, PlaTCOM held back the remaining funds of RM595K, and implemented a new SOP I had to follow if I wanted to qualify for disbursement, but more on this later.

Throughout Phase 2, PlaTCOM closely monitored our progress and was aware of the debts we took on.

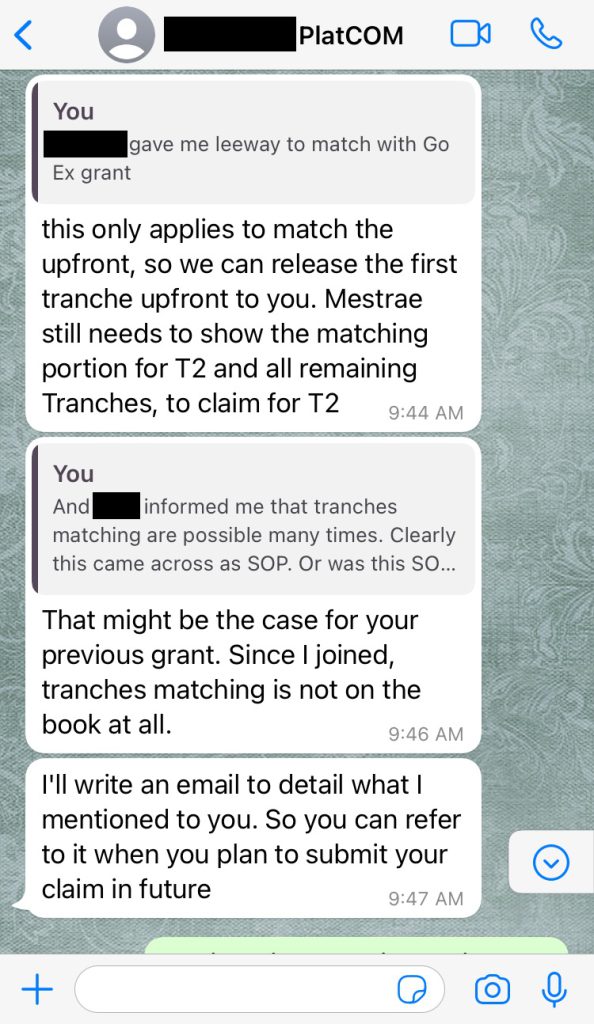

At the start of the project, the CEO accepted my request for tranche matching. However, PlaTCOM changed its SOP for disbursement after we completed everything, despite knowing our funds had dwindled.

We requested evaluation based on job completions, merits, and proof of payments but it was not accepted. All our accomplishments are public.

We started facing dire financial issues, struggling to make ends meet while creditors became increasingly agitated.

Lenders even resorted to physical and social media threats. Our team took pay cuts and late payments, and we started losing them one by one. Trust with friends and acquaintances who lent funds was hard to maintain.

After much persistence, PlatCOM agreed to request approval from the Steering Committee, comprising SME Corp, AIM, and PlatCOM.

For context, PlatCOM is a subsidiary of SME Corp, funded by SME Corp and governed by AIM. However, I was asked to wait for three months before the meeting could take place.

After three months’ wait, the Steering Committee rejected my disbursement request and refused to give a reason why.

A wild goose chase

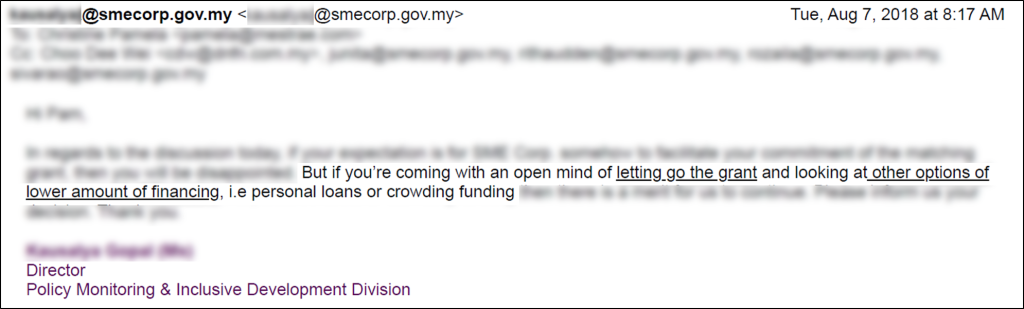

I contacted the SME Corp CEO for a meeting and was directed to the Director of the Policy Monitoring & Inclusive Development Division.

During the meeting, I asked how would someone like me, a mid-class and minority entrepreneur, find the necessary funding, and why my application wasn’t evaluated on its merits.

To my surprise, the policy director told me that if I didn’t have the money, forget the business and go home.

Despite the discouraging behavior, I insisted on finding solutions. But, instead of providing me with viable options, the policy director sent me on a wild goose chase, insisting I apply to organisations that were unable to provide the necessary funds.

In one of her emails, she even suggested that I drop the grant and settle for “lower funding,” completely ignoring the fact that I had already completed all the required tasks and achieved a global startup level.

This treatment felt like discrimination based on my middle-class status, and it was disheartening to be expected to settle for less.

Eventually, the policy director directed me back to PlaTCOM, falsely claiming that SME Corp had no involvement in the decision, even though the fund originated from the SME Corp funding pool.

At that time, PlaTCOM was dealing with internal audit issues, and the PlaTCOM CEO had already resigned and refused to respond to my attempts to communicate with him.

To make matters worse, this was when PlaTCOM changed the SOP once again, demanding that I produce a lump sum of RM310k cash in the bank overnight.

Although I was sceptical about the legitimacy of this request, I was unable to fulfill the requirement. As a result, the grant was terminated, citing my failure to comply with the “SOP” to the satisfaction of PlatCOM.

The accusation of “failure to comply with SOP” was unjust as it implied non-completion of tasks, while merits and achievements were repeatedly ignored.

What SME Corp and their subsidiary PlaTCOM did was damaging to my reputation, my business, and my credibility with vendors and customers.

Throughout this phase, I also went back to Cradle for their seed stage funds given we did well during the pre-seed stage.

Unfortunately, a senior exec of Cradle, who also oversaw the Malaysian Business Angel Network (MBAN) wanted 20% equity in my company in exchange for my receiving the grant, which I refused.

Exhausting my options

Desperate, I had to look for other options. I tried 12 private banks but they do not seem to favour fashion-related businesses. Meanwhile, government-backed loans have limitations if you have a grant contract and if you are a minority.

Race-based loans for minorities (TEKUN) are only available for micro-businesses. Creative industry-specific funding (MyCreative Ventures) required RM1 million revenue in the first year which is not feasible for startups.

Equity via venture capital in Malaysia is limited, and the early-stage funding pool is extremely small, with limited access for minorities.

Furthermore, investors are typically hesitant to fund businesses with heavy debt during the initial market penetration stage, and globally, women entrepreneurs encounter systemic issues, with only 2% receiving funding.

Equity crowdfunding back then was an expensive option requiring upfront bulk payment, a self-reliant aggregated pool of investors, and a harder bridge to Series A. Investors are also unlikely to support businesses with high debt in early market penetration stages. Hopefully, things have improved over time.

Money lenders were an option, but the high interest rates of up to 40% were what I would refer to as debt suicide.

The Asia Development Bank does not fund startups that are too small or too new, while the International Finance Corporation considers Malaysia a rich country, making it ineligible for funding. Factoring was another option, but banks require a high turnover of RM10 million yearly, which is not feasible for startups.

MATRADE facilitates trade but has reimbursement grants, which discriminate against mid-class entrepreneurs.

Its policies are outdated in a fast-paced digital commerce world. My experience with MATRADE involved an unclear mandate, arbitrary decision-making, and a lack of industry expertise, resulting in an incomplete disbursement.

Government grant agencies are the main accessible resources for entrepreneurs. However, only 15 of the 60 available grant agencies are publicly visible.

While many of these programmes are primarily geared toward Bumis, none of these programs publicly indicate who they fund, or the current status of the businesses funded.

Apart from mid-class discrimination and limited opportunities for minorities, startups also face additional hurdles of applying for grants from one agency to another for different purposes, which can consume a lot of time and resources.

Inflexible grant contracts can hinder startups from pivoting or modifying certain aspects of their core business or services, which is crucial for success. Furthermore, grants are often allocated broadly across industries, lacking industry specificity.

There are a lot more avenues that I tried but the stark reality remains that as a mid-income and minority entrepreneur, my options for economic assistance as a startup were extremely limited in Malaysia.

Half a million Ringgit of debt remains

For the rest of 2018, I tried to take in orders and even make part of the shoes myself as I couldn’t afford shoemakers. Furthermore, lenders were pursuing me, leading to non-stop legal matters and court cases.

If I am being honest, I was pretty burnt out. Despite it all, in 2019, we went on Kickstarter and raised almost 200% of our target. But due to court orders, our funds were mostly used to pay off debts.

The 2020 global pandemic lockdown resulted in 50% of SMEs shutting down and most of Mestrae’s suppliers were lost.

Malaysia’s footwear manufacturing resources have become limited, and the country’s rank in footwear exports dropped significantly.

During this lockdown phase, I completed an MBA (using EPF funds) and started consulting startups globally for income. I’ve been working non-stop, juggling multiple consulting jobs for the past few years trying to recover from debts and rebuild Mestrae. The lack of rest and overloaded stress were not kind to my health either.

While I am undeterred about continually moving forward, the harsh reality is that over half a million Ringgit of debt is an enormous burden for a mid-income person in Malaysia and is comparable to the cost of a home that can take up to decades to fully repay.

Over the years, PlaTCOM has been moved between SME Corp and AIM to JPM (Prime Minister’s Office) to MOSTI before shutting down. I am curious to know what happened to the money trail.

At present, MOSTI has absolved themselves of responsibility, citing that the funds are from SME Corp and that according to SME Corp, I “did not meet the SOP”. There was no evaluation based on merits.

Initially MOF followed up, but has since gone silent. When I recently contacted SME Corp, the policy director tried to mislead me again. I requested my reimbursement stating the intentional discrimination, but they have gone silent too.

Mestrae has the potential for rapid growth in the high-tech industry, clean tech, and global retail but it has to overcome its current debt obstacle caused by the government grant agency.

As the Prime Minister of Malaysia, YAB Dato Seri Anwar Ibrahim has been resilient and determined in bringing Malaysia forward, despite the struggles he endured.

I am confident he will look into the issue of middle-class oppression and minority limitation within the startup ecosystem in Malaysia. My sincere hope is that he will not remain silent too.

The startup ecosystem is holding entrepreneurs back

It’s hard to open up about the abuse and oppression that I faced. At first, I felt shattered and blamed myself.

As a struggling entrepreneur, I was afraid of burning bridges. Whenever I tried to bring this up, I was often made to feel like I was the problem, as the Malaysian startup ecosystem was portrayed as a bed of roses.

When I finally found the courage to share my story on my blog, I felt an enormous sense of relief. To my surprise, many entrepreneurs—mostly Bumi males—reached out and shared similar experiences of facing mid-class challenges with government agencies.

Their innovations were impressive, but they too struggled greatly. Some senior entrepreneurs shared similar encounters they faced 20 years back, and realised nothing has changed. Some of them have left the country.

Startup funds should be based on merits and potential. If startups and businesses are continually abused, Malaysia will not prosper.

Government agencies monopolise early-stage funding and often act as kingmakers, discriminating against mid-class entrepreneurs and minority groups, and treating them like criminals while corruption looms.

Additionally, the funds provided to Malaysian entrepreneurs are far below global benchmarking standards, falling short of 10%. Such practices must be eliminated if we hope to promote a culture of innovation and entrepreneurship.

Malaysia has incredible entrepreneurs. But the startup ecosystem is holding them back. It’s time to change that.

Featured Image Credit: Christine Pamela, Mestrae

Source link

Leave a Reply