I’ve given this blog post as a talk which you can watch here:

A while back, Guillermo Rauch (creator of

Socket.io and founder of Zeit.co (the

company behind a ton of the awesome stuff coming out lately))

tweeted something profound:

Write tests. Not too many. Mostly integration.

This is deep, albeit short, so let’s dive in:

Yes, for most projects you should write automated tests. You should if you value

your time anyway. Much better to catch a bug locally from the tests than getting

a call at 2:00 in the morning and fix it then. Often I find myself saving time

when I put time in to write tests. It may or may not take longer to implement

what I’m building, but I (and others) will almost definitely save time

maintaining it.

The thing you should be thinking about when writing tests is how much confidence

they bring you that your project is free of bugs. Static typing and linting

tools like TypeScript and

ESLint can get you a remarkable amount of confidence, and

if you’re not using these tools I highly suggest you give them a look. That

said, even a strongly typed language should have tests. Typing and linting

can’t ensure your business logic is free of bugs. So you can still seriously

increase your confidence with a good test suite.

I’ve heard managers and teams mandating 100% code coverage for applications.

That’s a really bad idea. The problem is that you get diminishing returns on

your tests as the coverage increases much beyond 70% (I made that number up…

no science there). Why is that? Well, when you strive for 100% all the time, you

find yourself spending time testing things that really don’t need to be tested.

Things that really have no logic in them at all (so any bugs could be caught by

ESLint and Flow). Maintaining tests like this actually really slow you and your

team down.

You may also find yourself testing implementation details just so you can make

sure you get that one line of code that’s hard to reproduce in a test

environment. You really want to avoid testing implementation details because

it doesn’t give you very much confidence that your application is working and it

slows you down when refactoring. You should very rarely have to change tests

when you refactor code.

I should mention that almost all of my open source projects have 100% code

coverage. This is because most of my open source projects are smaller libraries

and tools that are reusable in many different situations (a breakage could lead

to a serious problem in a lot of consuming projects) and they’re relatively easy

to get 100% code coverage on anyway.

There are all sorts of different types of testing (check out my 5 minute talk

about it at Fluent Conf:

“What we can learn about testing from the wheel”).

They each have trade-offs. The three most common forms of testing we’re talking

about when we talk of automated testing are: Unit, Integration, and End to End.

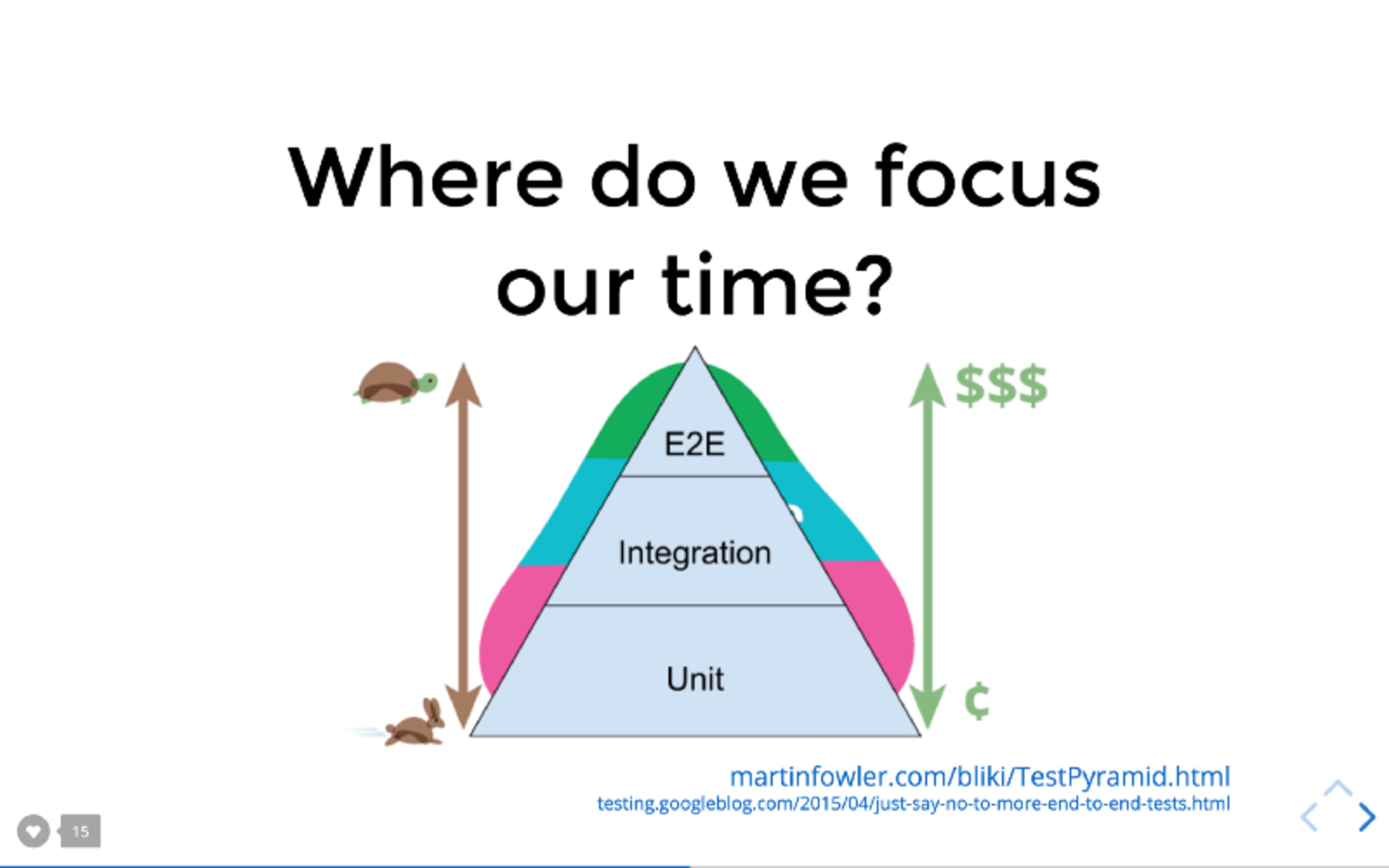

Here’s a slide from my

Frontend Masters workshop:

“Testing JavaScript Applications”.

This testing pyramid is a combination of one I got from

Martin Fowler’s blog and one

I got from

the Google Testing blog.

As indicated here, the pyramid shows from bottom to top: Unit, Integration, E2E.

As you move up the pyramid the tests get slower to write/run and more expensive

(in terms of time and resources) to run/maintain. It’s meant to indicate that

you should spend more of your time on unit tests due to these factors.

One thing that it doesn’t show though is that as you move up the pyramid, the

confidence quotient of each form of testing increases. You get more bang for

your buck. So while E2E tests may be slower and more expensive than unit tests,

they bring you much more confidence that your application is working as

intended.

As noted, our tools have moved beyond the assumption in Martin’s original

Testing Pyramid concept. This is why I created “The Testing Trophy” 🏆

Here’s a humorous other illustration of the importance of integration tests:

It doesn’t matter if your component <A /> renders component <B /> with props

c and d if component <B /> actually breaks if prop e is not supplied. So

while having some unit tests to verify these pieces work in isolation isn’t a

bad thing, it doesn’t do you any good if you don’t also verify that they

work together properly. And you’ll find that by testing that they work together

properly, you often don’t need to bother testing them in isolation.

Integration tests strike a great balance on the trade-offs between confidence

and speed/expense. This is why it’s advisable to spend most (not all, mind

you) of your effort there.

For more on this read Testing Implementation

Details. For more about the different

distinctions of tests, read Static vs Unit vs Integration vs E2E Testing for

Frontend Apps

The line between integration and unit tests is a little bit fuzzy. Regardless, I

think the biggest thing you can do to write more integration tests is to stop

mocking so much stuff. When you mock something you’re removing all confidence

in the integration between what you’re testing and what’s being mocked. I

understand that sometimes it can’t be helped

(though some would disagree). You don’t

actually want to send emails or charge credit cards every test, but most of

the time you can avoid mocking and you’ll be better for it.

If you’re doing React, then this includes shallow rendering. For more on

this, read

Why I Never Use Shallow Rendering.

I don’t think that anyone can argue that testing software is a waste of time.

The biggest challenge is knowing what to test

and how to test it in a way that gives

true confidence rather than the false

confidence of

testing implementation details.

I hope this is helpful to you and I wish you the best luck in your goals to find

confidence in shipping your applications!

Source link

Leave a Reply