In my interview “Testing Practices with

J.B. Rainsberger” available on

TestingJavaScript.com he gave me a metaphor I

really like. He said:

You can throw paint against the wall and eventually you might get most of the

wall, but until you go up to the wall with a brush, you’ll never get the

corners. 🖌️

I love that metaphor in how it applies to testing because it’s basically saying

that choosing the right testing strategy is the same kind of choice you’d make

when choosing a brush for painting a wall. Would you use a fine-point brush for

the entire wall? Of course not. That would take too long and the end result

would probably not look very even. Would you use a roller to paint everything,

including around the mounted furnishings your great-great-grandmother brought

over the ocean two hundred years ago? No way. There are different brushes for

different use cases and the same thing applies to tests.

This is why

I created the Testing Trophy.

Since then Maggie Appleton (the mastermind

behind egghead.io‘s masterful art/design) created this for

TestingJavaScript.com:

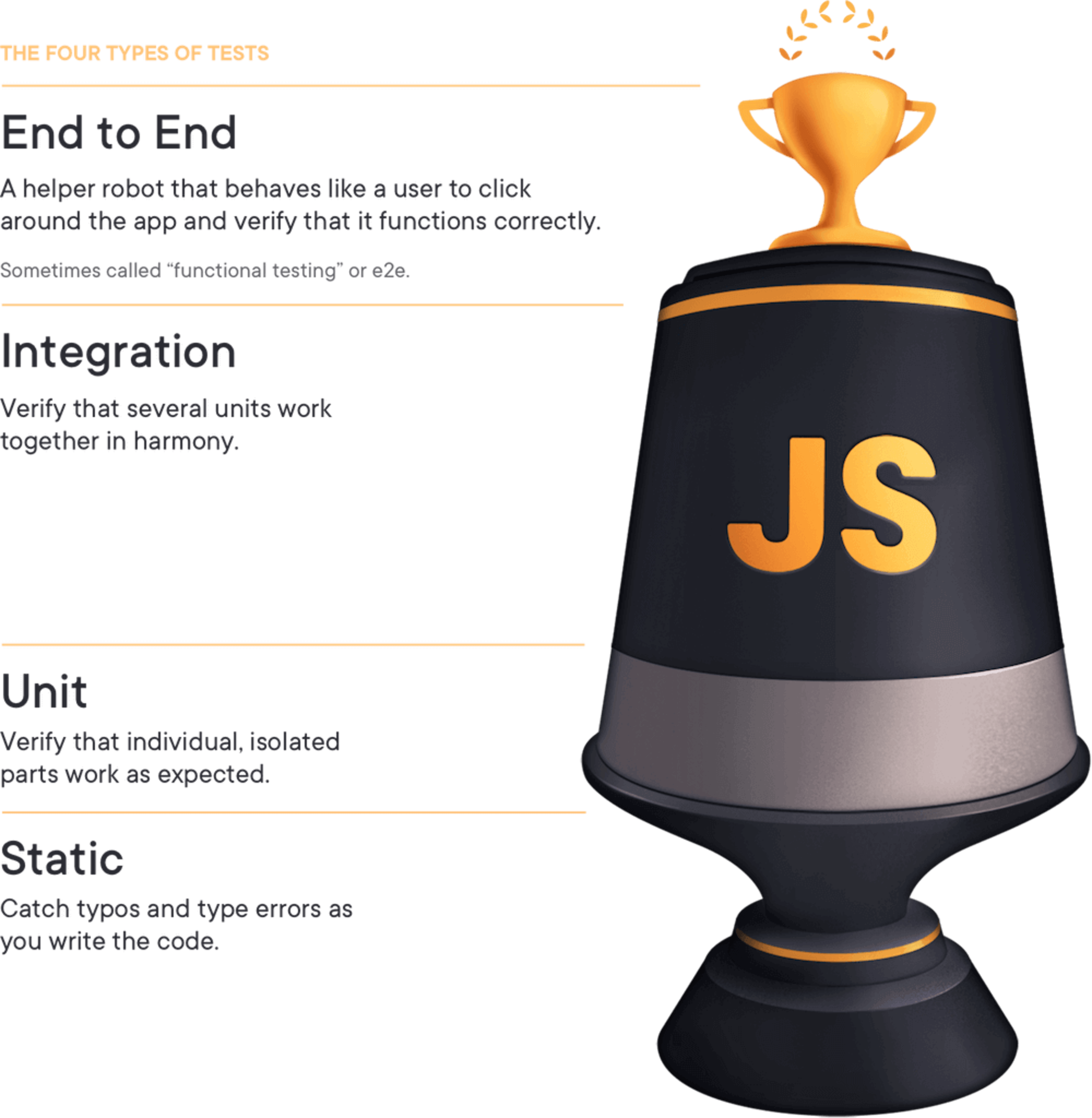

In the Testing Trophy, there are 4 types of tests. It shows this text above, but

for the sake of those using assistive technologies (and in case the image fails

to load for you), I’ll write out what it says here from top to bottom:

- End to End: A helper robot that behaves like a user to click around the

app and verify that it functions correctly. Sometimes called “functional

testing” or e2e. - Integration: Verify that several units work together in harmony.

- Unit: Verify that individual, isolated parts work as expected.

- Static: Catch typos and type errors as you write the code.

The size of these forms of testing on the trophy is relative to the amount of

focus you should give them when testing your applications (in general). I want

to take a deep dive on these different forms of testing, what it means

practically, and what we can do to optimize for the greatest bang for our

testing buck.

Let’s look at a few examples of what these kinds of tests are, going from top to

bottom:

End to End

Typically these will run the entire application (both frontend and backend) and

your test will interact with the app just like a typical user would. These tests

are written with cypress.

import {generate} from 'todo-test-utils'

describe('todo app', () => {

it('should work for a typical user', () => {

const user = generate.user()

const todo = generate.todo()

// here we're going through the registration process.

// I'll typically only have one e2e test that does this.

// the rest of the tests will hit the same endpoint

// that the app does so we can skip navigating through that experience.

cy.visitApp()

cy.findByText(/register/i).click()

cy.findByLabelText(/username/i).type(user.username)

cy.findByLabelText(/password/i).type(user.password)

cy.findByText(/login/i).click()

cy.findByLabelText(/add todo/i)

.type(todo.description)

.type('{enter}')

cy.findByTestId('todo-0').should('have.value', todo.description)

cy.findByLabelText('complete').click()

cy.findByTestId('todo-0').should('have.class', 'complete')

// etc...

// My E2E tests typically behave similar to how a user would.

// They can sometimes be quite long.

})

})

Integration

The test below renders the full app. This is NOT a requirement of integration

tests and most of my integration tests don’t render the full app. They will

however render with all the providers used in my app (that’s what the render

method from the imaginary “test/app-test-utils” module does). The idea behind

integration tests is to mock as little as possible. I pretty much only mock:

- Network requests (using MSW)

- Components responsible for animation (because who wants to wait for that in

your tests?)

import * as React from 'react'

import {render, screen, waitForElementToBeRemoved} from 'test/app-test-utils'

import userEvent from '@testing-library/user-event'

import {build, fake} from '@jackfranklin/test-data-bot'

import {rest} from 'msw'

import {setupServer} from 'msw/node'

import {handlers} from 'test/server-handlers'

import App from '../app'

const buildLoginForm = build({

fields: {

username: fake(f => f.internet.userName()),

password: fake(f => f.internet.password()),

},

})

// integration tests typically only mock HTTP requests via MSW

const server = setupServer(...handlers)

beforeAll(() => server.listen())

afterAll(() => server.close())

afterEach(() => server.resetHandlers())

test(`logging in displays the user's username`, async () => {

// The custom render returns a promise that resolves when the app has

// finished loading (if you're server rendering, you may not need this).

// The custom render also allows you to specify your initial route

await render(<App />, {route: '/login'})

const {username, password} = buildLoginForm()

userEvent.type(screen.getByLabelText(/username/i), username)

userEvent.type(screen.getByLabelText(/password/i), password)

userEvent.click(screen.getByRole('button', {name: /submit/i}))

await waitForElementToBeRemoved(() => screen.getByLabelText(/loading/i))

// assert whatever you need to verify the user is logged in

expect(screen.getByText(username)).toBeInTheDocument()

})

For these, I’ll also typically have a few things configured globally like

automatically resetting all mocks

between tests.

Learn how to setup a test-utils file like the one above in the

React Testing Library setup docs.

Unit

import '@testing-library/jest-dom/extend-expect'

import * as React from 'react'

// if you have a test utils module like in the integration test example above

// then use that instead of @testing-library/react

import {render, screen} from '@testing-library/react'

import ItemList from '../item-list'

// Some people don't call these a unit test because we're rendering to the DOM with React.

// They'd tell you to use shallow rendering instead.

// When they tell you this, send them to https://kcd.im/shallow

test('renders "no items" when the item list is empty', () => {

render(<ItemList items={[]} />)

expect(screen.getByText(/no items/i)).toBeInTheDocument()

})

test('renders the items in a list', () => {

render(<ItemList items={['apple', 'orange', 'pear']} />)

// note: with something so simple I might consider using a snapshot instead, but only if:

// 1. the snapshot is small

// 2. we use toMatchInlineSnapshot()

// Read more: https://kcd.im/snapshots

expect(screen.getByText(/apple/i)).toBeInTheDocument()

expect(screen.getByText(/orange/i)).toBeInTheDocument()

expect(screen.getByText(/pear/i)).toBeInTheDocument()

expect(screen.queryByText(/no items/i)).not.toBeInTheDocument()

})

Everyone calls this a unit test and they’re right:

// pure functions are the BEST for unit testing and I LOVE using jest-in-case for them!

import cases from 'jest-in-case'

import fizzbuzz from '../fizzbuzz'

cases(

'fizzbuzz',

({input, output}) => expect(fizzbuzz(input)).toBe(output),

[

[1, '1'],

[2, '2'],

[3, 'Fizz'],

[5, 'Buzz'],

[9, 'Fizz'],

[15, 'FizzBuzz'],

[16, '16'],

].map(([input, output]) => ({title: `${input} => ${output}`, input, output})),

)

Static

// can you spot the bug?

// I'll bet ESLint's for-direction rule could

// catch it faster than you in a code review 😉

for (var i = 0; i < 10; i--) {

console.log(i)

}

const two = '2'

// ok, this one's contrived a bit,

// but TypeScript will tell you this is bad:

const result = add(1, two)

I think it’s important to remember why it is that we write tests in the first

place. Why do you write tests? Is it because I told you to? Is it because your

PR will get rejected unless it includes tests? Is it because testing enhances

your workflow?

The biggest and most important reason that I write tests is CONFIDENCE. I

want to be confident that the code I’m writing for the future won’t break the

app that I have running in production today. So whatever I do, I want to make

sure that the kinds of tests I write bring me the most confidence possible and I

need to be cognizant of the trade-offs I’m making when testing.

There are some important elements to the testing trophy I want to call out in

this picture (ripped from my slides):

The arrows on the image signify three trade-offs you make when writing automated

tests:

Cost: ¢ heap ➡ 💰🤑💰

As you move up the testing trophy, the tests become more costly. This comes in

the form of actual money to run the tests in a continuous integration

environment, but also in the time it takes engineers to write and maintain each

individual test.

The higher up the trophy you go, the more points of failure there are and

therefore the more likely it is that a test will break, leading to more time

needed to analyze and fix the tests. Keep this in mind because it’s

important #foreshadowing…

Speed: 🏎💨 ➡ 🐢

As you move up the testing trophy, the tests typically run slower. This is due

to the fact that the higher you are on the testing trophy, the more code your

test is running. Unit tests typically test something small that has no

dependencies or will mock those dependencies (effectively swapping what could be

thousands of lines of code with only a few). Keep this in mind because it’s

important #foreshadowing…

Confidence: Simple problems 👌 ➡ Big problems 😖

The cost and speed trade-offs are typically referenced when people talk about

the testing pyramid 🔺. If those were the only trade-offs though, then I would

focus 100% of my efforts on unit tests and totally ignore any other form of

testing when regarding the testing pyramid. Of course we shouldn’t do that and

this is because of one super important principle that you’ve probably heard me

say before:

The more your tests resemble the way your software is used, the more confidence they can give you.

What does this mean? It means that there’s no better way to ensure that your

Aunt Marie will be able to file her taxes using your tax software than actually

having her do it. But we don’t want to wait on Aunt Marie to find our bugs for

us right? It would take too long and she’d probably miss some features that we

should probably be testing. Compound that with the fact that we’re regularly

releasing updates to our software there’s no way any amount of humans would be

able to keep up.

So what do we do? We make trade-offs. And how do we do that? We write

software that tests our software. And the trade-off we’re always making when we

do that is now our tests don’t resemble the way our software is used as reliably

as when we had Aunt Marie testing our software. But we do it because we solve

real problems we had with that approach. And that’s what we’re doing at every

level of the testing trophy.

As you move up the testing trophy, you’re increasing what I call the

“confidence coefficient.” This is the relative confidence that each test can

get you at that level. You can imagine that above the trophy is manual testing.

That would get you really great confidence from those tests, but the tests would

be really expensive and slow.

Earlier I told you to remember two things:

- The higher up the trophy you go, the more points of failure there are and

therefore the more likely it is that a test will break- Unit tests typically test something small that has no dependencies or will

mock those dependencies (effectively swapping what could be thousands of

lines of code with only a few).

What those are saying is that the lower down the trophy you are, the less code

your tests are testing. If you’re operating at a low level you need more tests

to cover the same number of lines of code in your application as a single test

could higher up the trophy. In fact, as you go lower down the testing trophy,

there are some things that are impossible to test.

In particular, static analysis tools are incapable of giving you confidence in

your business logic. Unit tests are incapable of ensuring that when you call

into a dependency that you’re calling it appropriately (though you can make

assertions on how it’s being called, you can’t ensure that it’s being called

properly with a unit test). UI Integration tests are incapable of ensuring that

you’re passing the right data to your backend and that you respond to and parse

errors correctly. End to End tests are pretty darn capable, but typically you’ll

run these in a non-production environment (production-like, but not production)

to trade-off that confidence for practicality.

Let’s go the other way now. At the top of the testing trophy, if you try to use

an E2E test to check that typing in a certain field and clicking the submit

button for an edge case in the integration between the form and the URL

generator, you’re doing a lot of setup work by running the entire application

(backend included). That might be more suitable for an integration test. If you

try to use an integration test to hit an edge case for the coupon code

calculator, you’re likely doing a fair amount of work in your setup function to

make sure you can render the components that use the coupon code calculator and

you could cover that edge case better in a unit test. If you try to use a unit

test to verify what happens when you call your add function with a string

instead of a number you could be much better served using a static type checking

tool like TypeScript.

Every level comes with its own trade-offs. An E2E test has more points of

failure making it often harder to track down what code caused the breakage, but

it also means that your test is giving you more confidence. This is especially

useful if you don’t have as much time to write tests. I’d rather have the

confidence and be faced with tracking down why it’s failing, than not having

caught the problem via a test in the first place.

In the end I don’t really care about the distinctions. If you want to call

my unit tests integration tests or even E2E tests (as some people have 🤷♂️) then

so be it. What I’m interested in is whether I’m confident that when I ship my

changes, my code satisfies the business requirements and I’ll use a mix of the

different testing strategies to accomplish that goal.

Good luck!

Leave a Reply